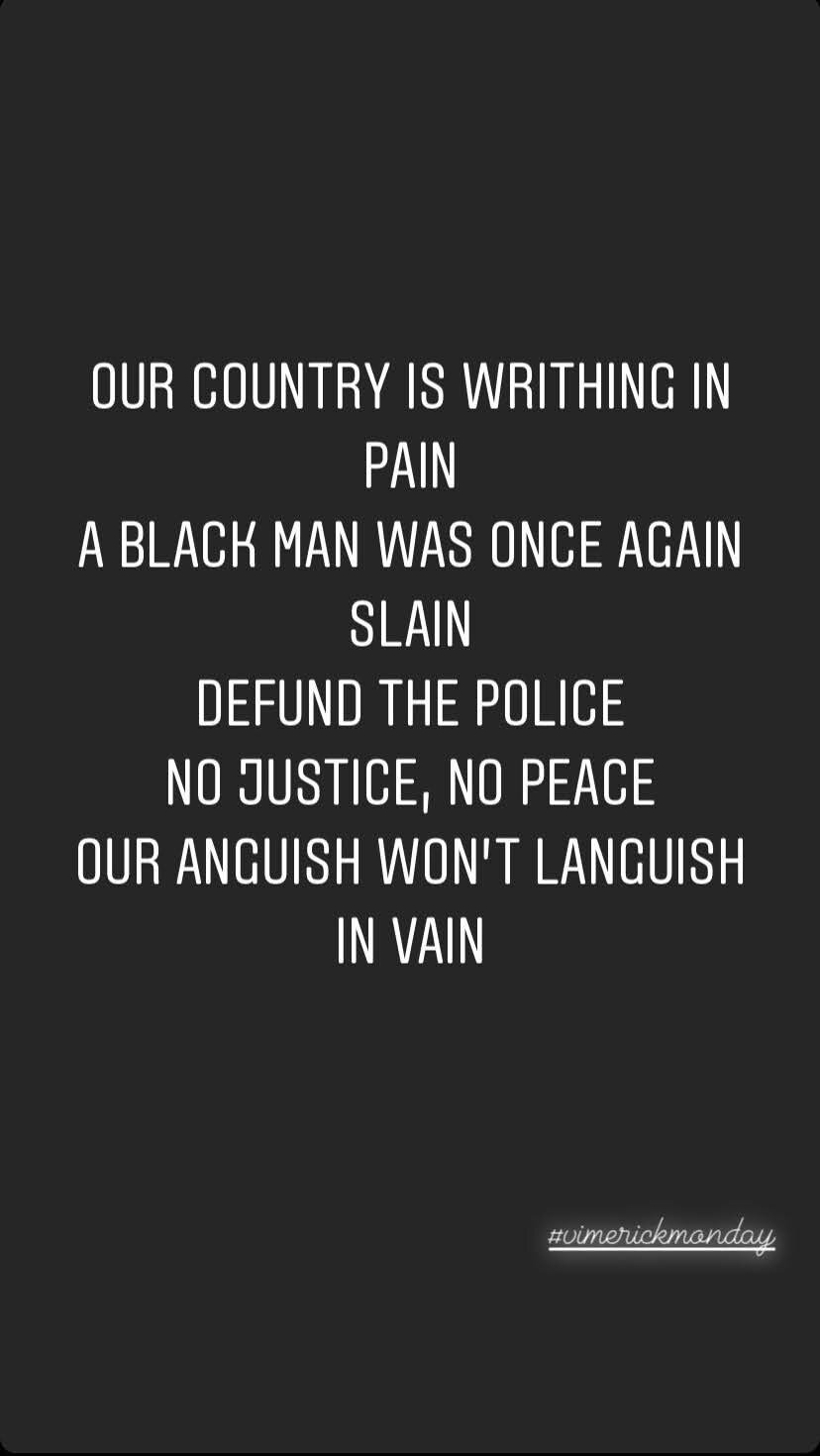

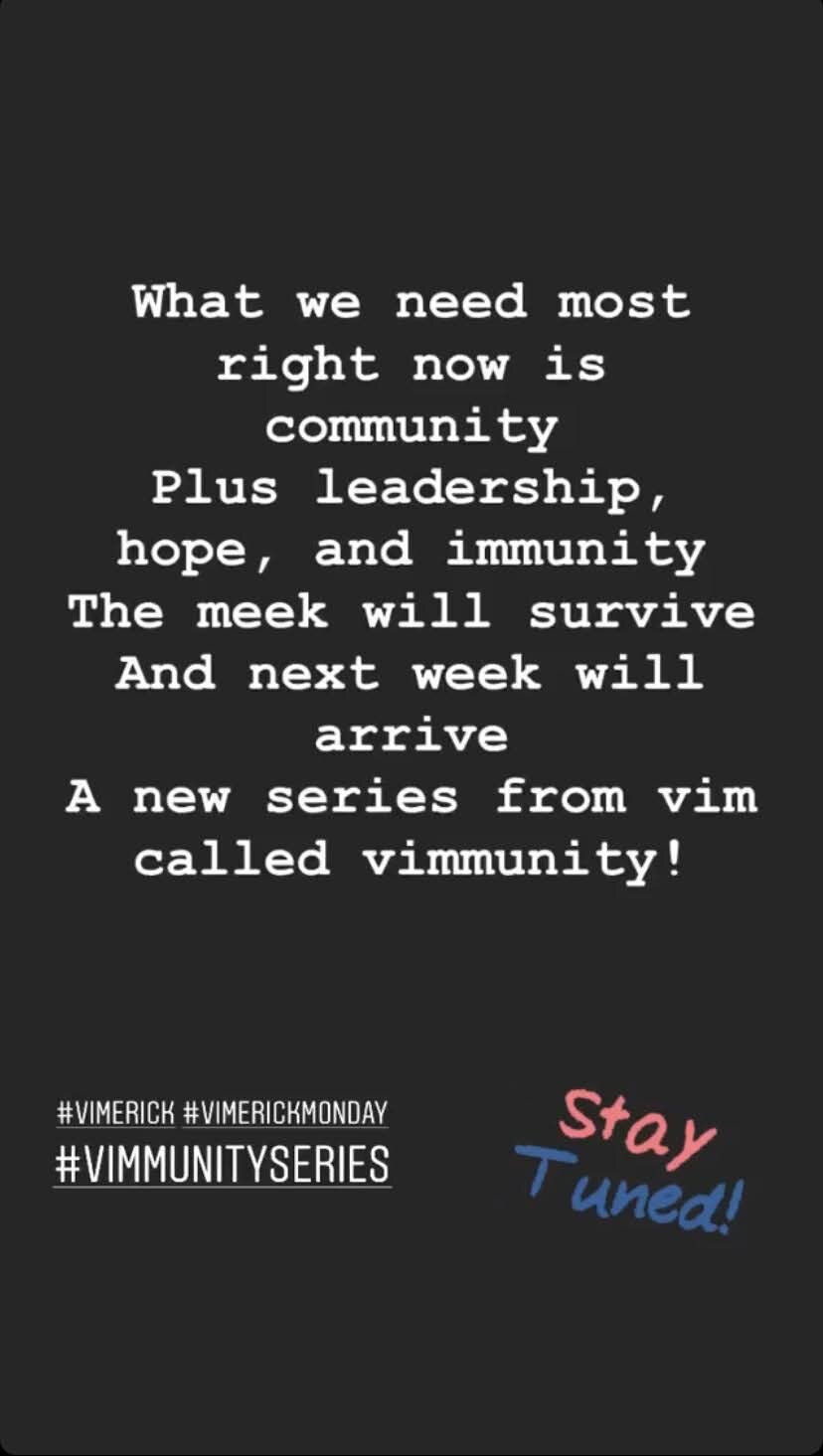

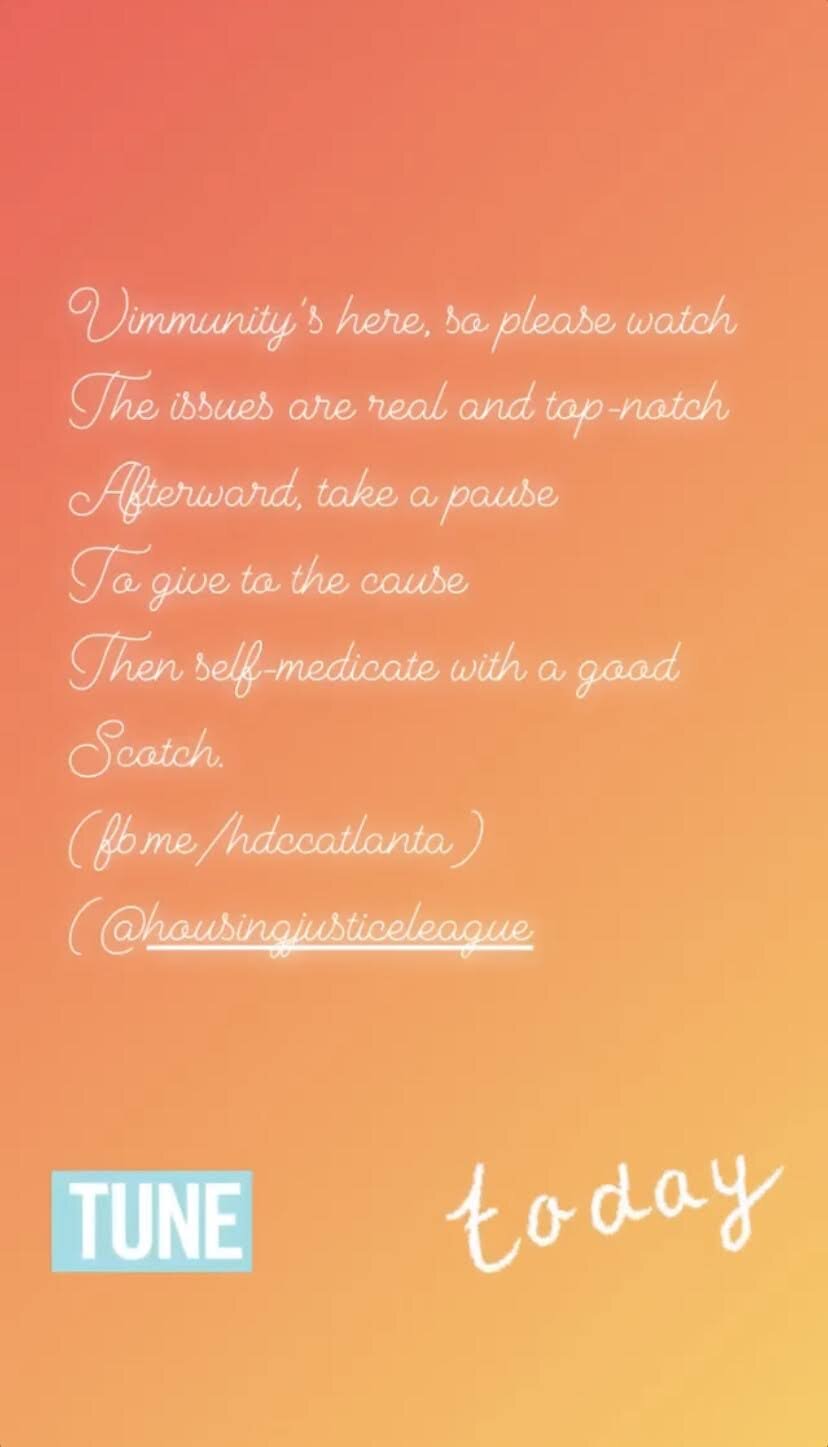

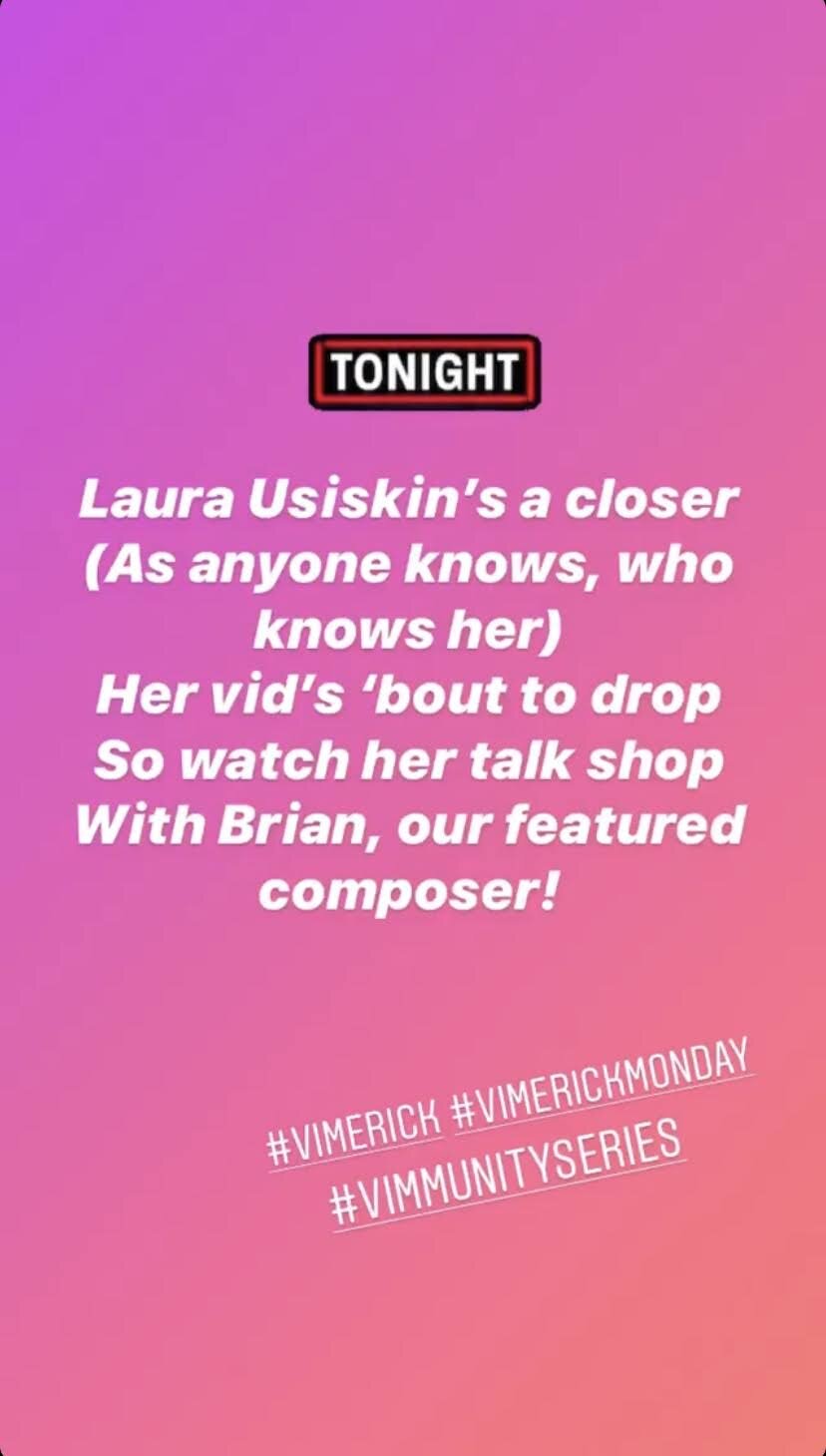

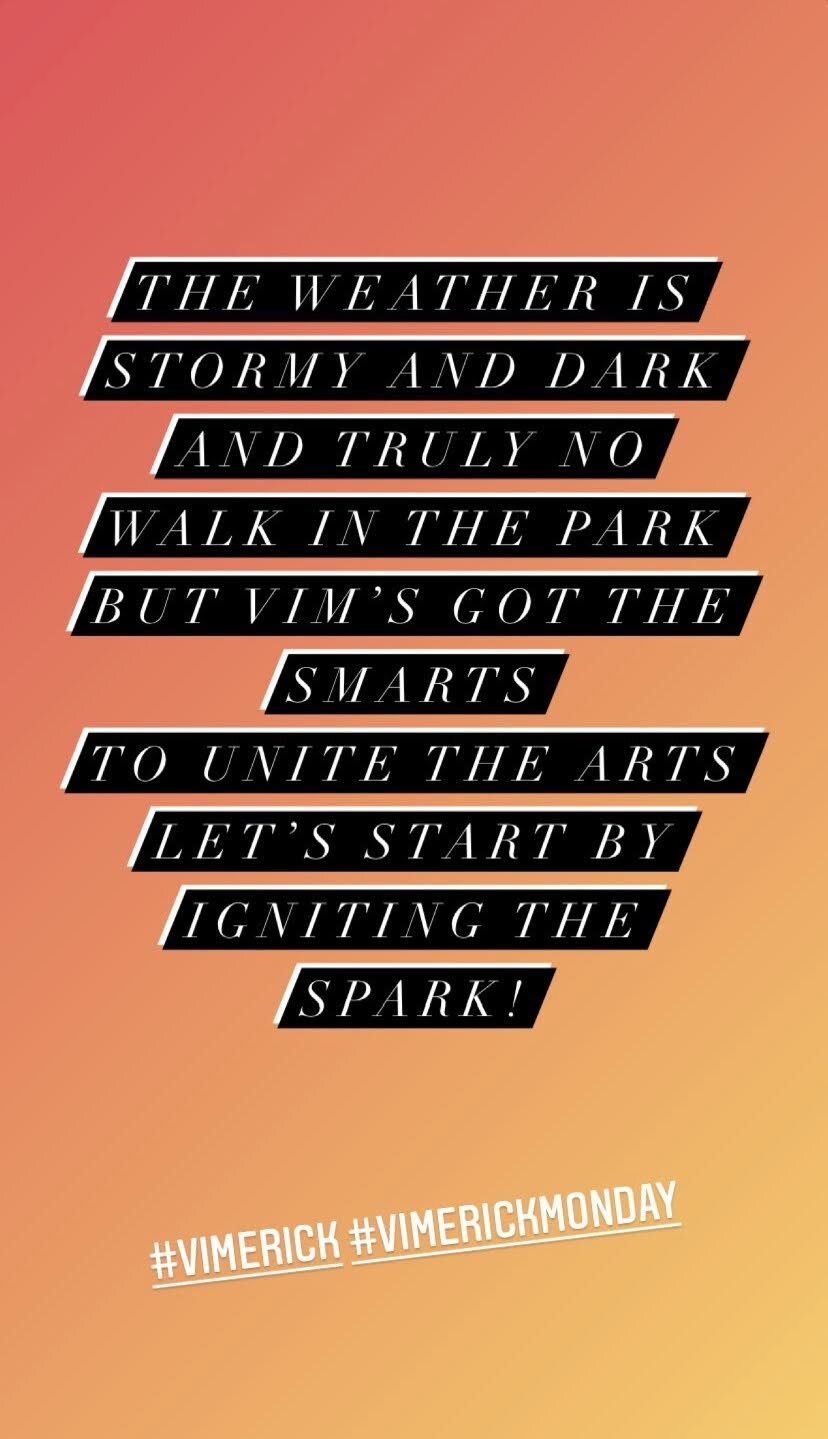

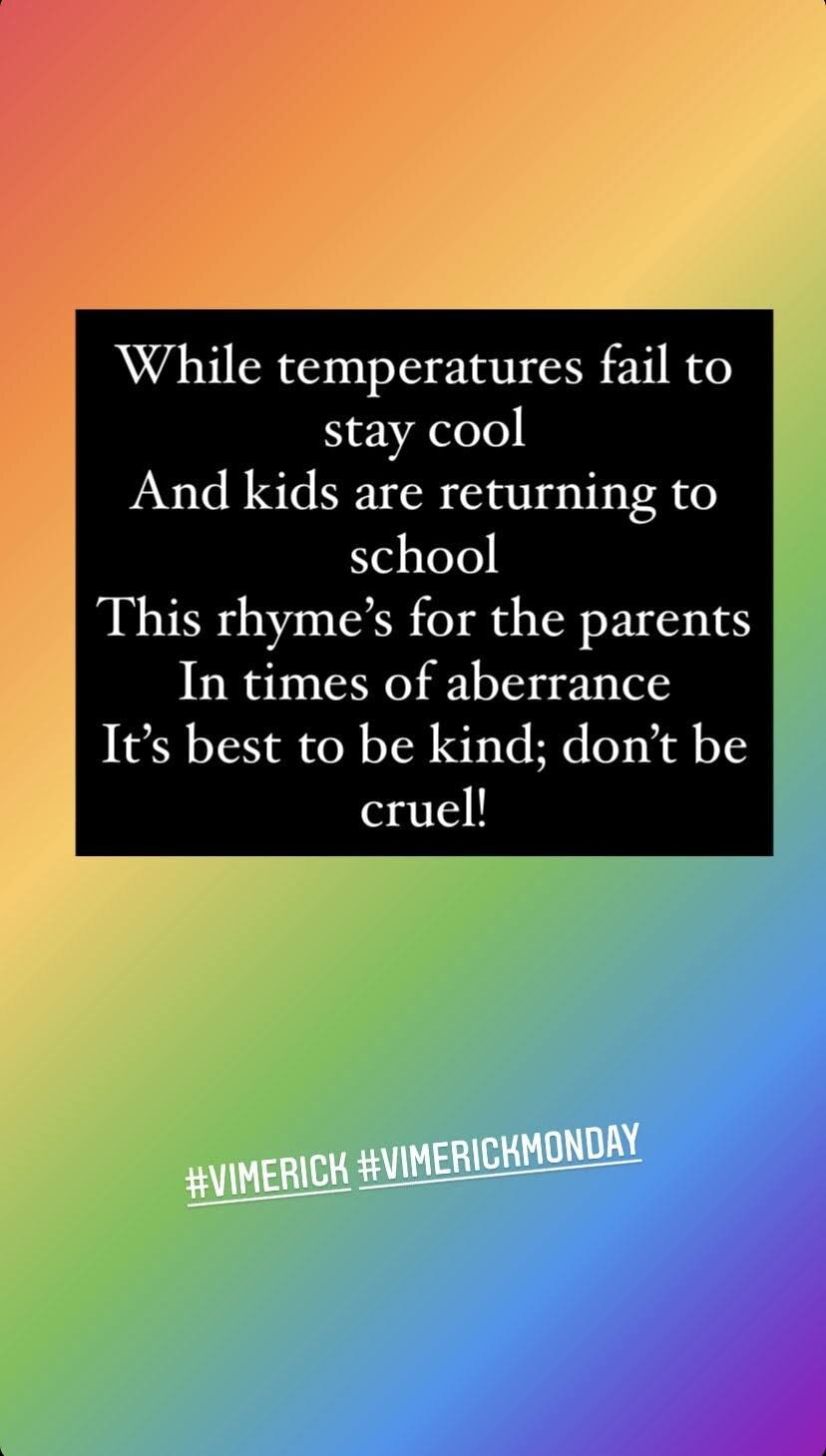

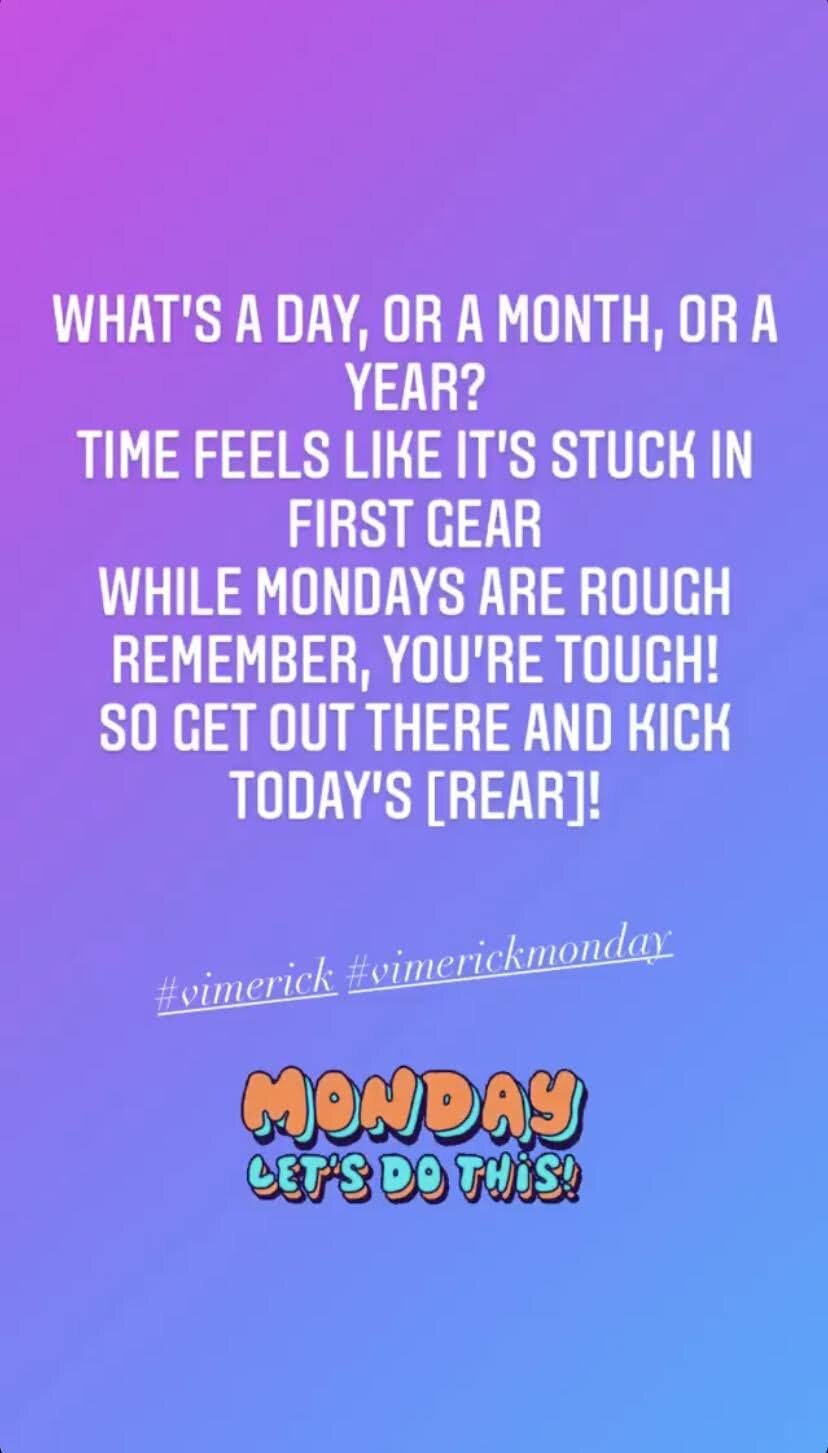

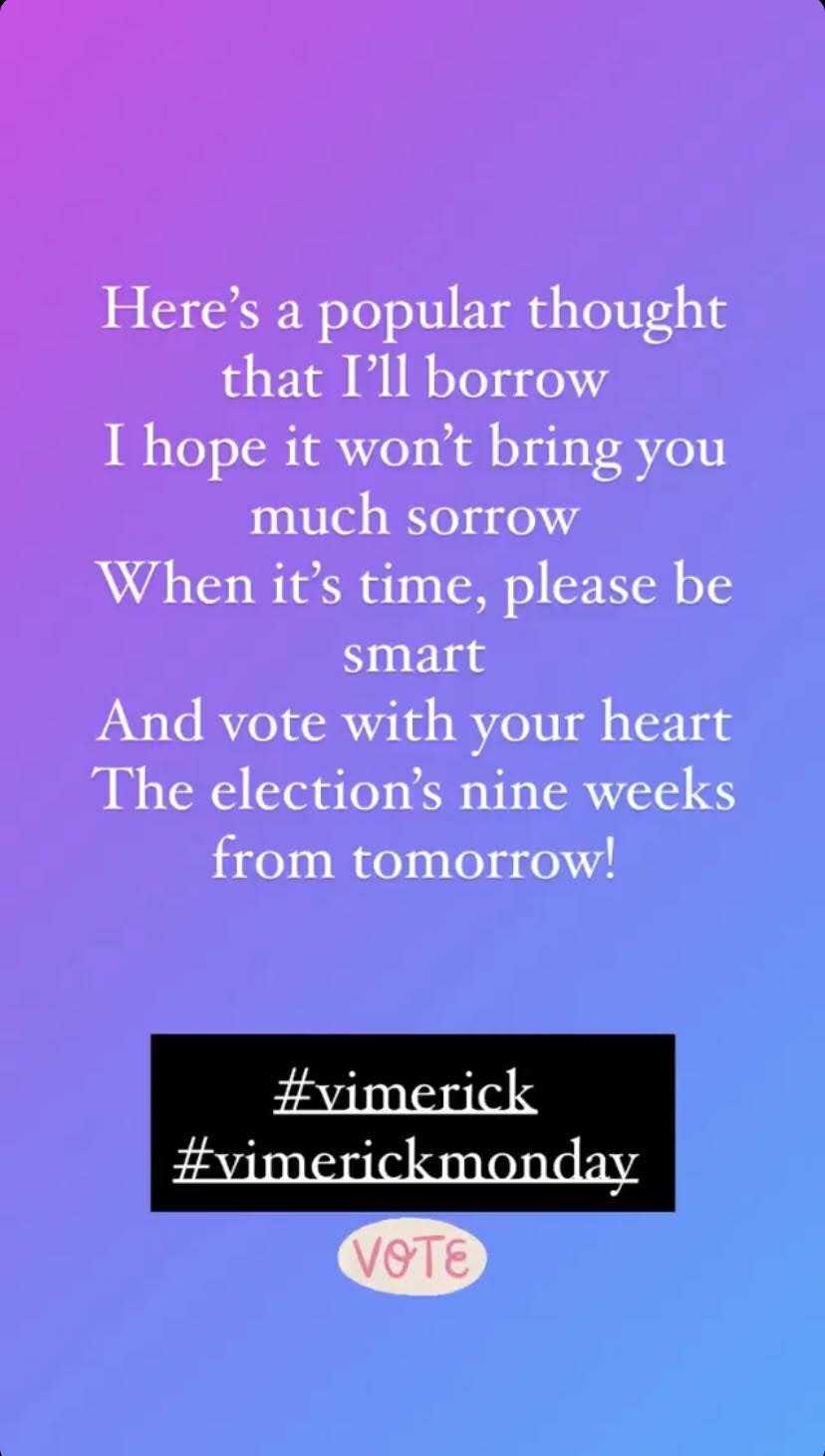

Here you can scroll through our archive of weekly vimericks, composed by our pianist, Choo Choo, and posted every Monday to our Instagram stories and highlights!

Here you can scroll through our archive of weekly vimericks, composed by our pianist, Choo Choo, and posted every Monday to our Instagram stories and highlights!

Like great art, my greatest music lessons always had a universality to them. They were focused not so much on how to play the instrument, but on how the music interacts within the limits of physics above the subatomic level. My teacher liked to discuss physics a lot in our lessons. Everything was about momentum, centrifugal/centripetal force, antigravity, the cosmos. Posters of dazzling images from the Hubble telescope plastered his studio walls. Each time I left that room I felt a heady sense of communion with the forces of art and nature, the vastness of the universe presenting itself to me in the grumbling fanfare of a Beethoven sonata or Brahms concerto.

Leading up to ensemble vim’s inaugural concert this weekend (Sunday at 4, Kellett Chapel, don’t be late!), I wanted to share three key things I’ve learned from my decades of music lessons. It’s taken years of self-study and measured reflection to let these aphorisms gel into something like a personal manifesto. If these tenets are all that stuck with me from my student days, I’ll consider it a victory. They may seem simplistic, trite even, something you might find on a school motivational poster or scattered around the home of someone with too much “Live, Laugh, Love” decor. I encourage you to see past my admittedly uninventive bullet points to the meat of the message. All three of these lessons can be applied microscopically, to specific musical problems, and macroscopically, to life, the universe, and everything (shout-out to Douglas Adams, because I’m a nerd like that):

1. Listen

So many of life’s problems would be alleviated if everyone listened a little better. Not just more; better. Don’t put on a sympathetic “I’m listening” face while inside you’re secretly crafting a witty anecdote or devastating comeback to parry as soon as your dialogue partner shuts up (I’ve been just as guilty of this as all of you). Really listening means setting your ego aside and valuing what others contribute to the conversation with no expectation of changing their mind or the topic. If most people did this, 24- hour news networks would go out of business overnight.

I’ve been in countless chamber music and orchestral settings where it’s so clear that everyone is so wrapped up in their own individual part that they

have no clue how it fits in with the rest of the group. Only after several rehearsals—of listening to the other parts, understanding the big picture— does it finally start to click. First of all, this can be remedied with better score study on the individual’s part. Learning your own part out of context from the piece as a whole is lazy and ineffective. It must also be so terrifying to show up to the first rehearsal without any idea of how the rest of the piece sounds. “Welp, I hope everyone is counting exactly the way I am! Here goes nothing...” Guaranteed recipe for crashing and burning. Been guilty of this too. It doesn’t take long before you realize people don’t like to work with these types of folk.

2. Expect the Unexpected

Life throws you curveballs. In a high-stakes, nervous-energy performance setting, things will inevitably stray from the controlled setting of your practice room. Plan for this. Practice playing in front of audiences. Prepare your music twice as well as you think you need to. Things will probably still go off course. That’s life. You can control your own part in it, but the chances of you being able to control anyone else’s decisions, their preparation, their dedication, are about as good as your chance of winning the Mega-Millions. Focus on being as solid as you can be in your part. And listen. And adjust.

Sometimes, in life and music, situations happen that are entirely beyond any preparation you could have done. The sudden illness of a family member, the snapping of an E string right in the middle of a big solo, the winning of the aforesaid Mega-Millions (in which case, congrats, can I have just like a couple mil? Even one would be great). The person who is adaptable and willing to accept the situation and spring into action to accommodate these new challenges will always fare better than the one who wrings their hands and proceeds to throw themselves the pity party of the century. There is a time and place for wallowing. But during that time you spent kvetching about how orchestral auditions are rigged and the system is broken, Caroline* was busy practicing her face off and winning that job you wanted. If you always play the victim, you’ll always be the victim.

*totally made up name, not based on fact

3. Timing is Everything

This might be the most clichéd of all the adages, but also (I think) the most important, and something I’ve lived by for a long time. My teacher, the one so enamored of physics and the universe, took an Einsteinian approach to rhythm. Instead of conceiving of time as a fixed constant, as we were all taught to do as dutiful young music students (one, two, three, four, turn that metronome on and turn your brain off and stick with it, dammit!), he understood that there was room to bend and compress the phrase, as long as it stayed within the larger metric parameters. I can’t stress the importance of this last clause enough. One of my biggest musical pet peeves is when a performer clearly has no sense of the rhythmic structure, and has just approximated the rhythm or taken time here and there because the spirit moved them, or (heaven forbid) “That’s how everyone else does it.” Is that what the composer wrote? Could you achieve the same result while attempting to stay faithful to the instructions on the page?

People conceive of time differently. The nature of one’s instrument will have an effect on this; percussive instruments (I’ll include piano in this for categorical purposes, but this is a philosophical pondering for another blog post) have an immediate reaction from the time the note is played to its acceptance by the ear. Winds and brass require a level of anticipation because they have to account for this pesky thing called breathing. Similarly for string players, where there is a slight delay as bow drags across string. I lament the fact that many beginner students of these disciplines don’t spend enough time on rhythm. It makes sense; with problems like intonation and bowing and just trying to make a pleasing sound (have you ever been to a beginner strings recital? You brave soul, you), it’s no wonder rhythm takes lower billing. I always tell my students that rhythm is the single-most important aspect of music. Just like in life, if you meet the right person at the wrong time, technically they’re the wrong person; in music, if you play the right note at the wrong time, it’s the wrong note. You can imagine this is amplified by comical degrees when it comes to playing in a new music ensemble.

Personally, I believe all beginner music students should learn rhythm like a percussionist. I’ll fight anyone on this, so come at me, bro.

There it is. If you stuck with me through all of this and you’re not my lovely boyfriend who I made proof-read this, thank you, and I hope you got something out of it. Also, why? I should probably shower and head to rehearsal. Atlanta traffic is always an exercise in expecting the unexpected, and I pride myself (in professional situations only!) on always arriving on time.

-Choo Choo Hu, piano

As my colleagues and I plotted an underlying theme for our inaugural season, I began to think about the nature of chamber music, or of any successful collaboration. It’s no secret to anyone who knows me that chamber music is my favorite type of musical genre, both to play and hear. There is something unspeakably satisfying about connecting with a small group of like-minded musicians all with the shared goal of producing a sublime performance. Just like any relationship, some of these collaborations are more fulfilling than others. Some of them require a lot of work to achieve worthwhile results. But there is comfort in the doing, in the mere attempt. Chamber music is equal parts chess and double dutch swaddled in a narrative blanket. It is strategy and harmony bound by storytelling.

On our November 10 mainstage concert, vim is performing the devilishly clever “Workers Union” by Louis Andriessen. This will test our mettle as an ensemble, since the whole group is required to be in strict rhythmic unison throughout the unspecified (to be determined by the group) duration of the piece. It is written for any number of instruments, and is melodically indeterminate. The composer himself writes, “This piece is a combination of individual freedom and severe discipline: its rhythm is exactly fixed; the pitch, on the other hand, is indicated only approximately, on a single-lined stave. It is difficult to play in an ensemble and to remain in step, sort of like organizing and carrying on political action.”

In a world whose collective political action seems to toggle from mildly unsettling to deeply offensive in the blink of a tweet, I can take solace in the fact that, at least in my little corner of the world, I have a group of fierce individuals who have agreed to tuck themselves in to this chess rope blanket with me and see what transpires. For the common good.

(Also if you’re not familiar with my writing, get ready for a lot of semi-confusing metaphors from here on out.)

-Choo Choo Hu, piano

My parents moved from China to St. Louis when I was two years old. In many ways, ours is the quintessential immigrant story. We were unimaginably poor; my dad was a student, and to support us my mom worked fourteen-hour shifts as a cook in a Chinese takeout restaurant, making two dollars an hour. But as difficult as times were, I never felt like we were struggling or that we had less than others. My mom scrimped and saved, and there was always food on the table, and the bills were always paid on time. When I was a little girl, as soon as I knew how to hold a pen, I would spend hours every day by myself, with a notebook and pencil, scribbling and drawing and writing over and over the two or three words I knew how to spell, creating my own little stories. My parents encouraged this behavior, since they knew that other forms of entertainment were costly. My creativity and imagination were my playground. When I discovered reading, a whole universe opened up to me. Suddenly I could disappear into other worlds, travel to exotic lands without ever leaving my bedroom. I met all kinds of people between the pages of my books, making friends with some of them, enemies with others, learning about the world and about how I viewed the world with every turn of a page. Reading was a way for me to spend hours upon hours alone, yet I never felt lonely.

When I was five years old my parents used what little leftover savings they had to send me to piano lessons. Suddenly my world expanded even more. If reading opened up new worlds, music opened up whole other dimensions. It was as if someone had taken the feelings we all have that words can’t express, and brought them to life. Practicing piano every day was a way for me to get lost in my thoughts, to block out whatever real-world problems I was having and just spend a few minutes being transported to someplace better, nicer, less cold and complicated.

So from a very young age, I knew that music, art, and literature were my safe spaces. An escape from the pressures of the outside world, a place where I could retreat when the going got tough. I’ve always been perfectly happy spending lots of time by myself and not feeling like I’m missing out on anything. I credit that comfort with isolation to these imaginary worlds inside my head, between the pages of a book and the notes on a sheet of music.

-Choo Choo Hu, piano